French pioneer apothecary Louis Hébert was the first European farmer in Canada. Cannabis Sativa, a plant known as “hemp,” was one of his crops.

The sails of sailing ships, canvas, rope, and linen were all manufactured from the rugged fibres of the hemp plant. As was the earliest known paper. Hemp dominated the paper trade until it was replaced by wood fibre in the 1800s.

When the Indian strain of Cannabis that had been used in Eastern medicine for thousands of years became a popular ingredient in 19th Century Western medicine, French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck “came up with the name Cannabis indica to distinguish Indian cannabis from European hemp.”

War On Drugs

There were no illegal drugs in Canada prior to the 20th Century. Deputy Minister of Labour William Lyon MacKenzie King changed all that in 1908.

“On Sept. 7, 1907, the Asiatic Exclusion League of Vancouver went on a rampage though the city’s Chinatown and Little Tokyo. No one was killed, but there was considerable property damage.

“The Liberal government of Wilfrid Laurier sent William Lyon Mackenzie King, the country’s first deputy minister of labour, to investigate.”Among the many individuals who submitted claims for restitution were several Chinese opium dealers, which prompted King to study the opium trade in Vancouver.

“There were no laws then governing the use of opium or other drugs; and, in fact, during the 19th century, laudanum, a mixture of liquid opium and alcohol and highly addictive, was popular as a pain remedy.

“King was stunned by what he learned about the corrupting influence of opium, connected as it was with widespread notions that Chinese men used opium to exploit and sexually assault white women.”

Rather than formulating policy to address Vancouver’s anti-immigrant racism, the Government based its first drug law, the Opium Act of 1908, on the Report by W. L. Mackenzie King, C.M.G., Deputy Minister of Labour, on “The Need for the Suppression of Opium Traffic in Canada.”

A year later the Canadian Government instituted the first legislation to regulate the use of medicine to protect the public in The Proprietary or Patent Medicine Act (1909). As an ingredient used in many such medicines, cannabis was regulated by this act.

The illicit opium smuggling that sprang up in answer to the Opium Act warranted a Royal Commission. Its recommendations to:

- make sale, possession & smoking illegal drugs separate offenses, and

- increase the power of police search and seizure

were incorporated in the “Act to Prohibit the Improper Use of Opium and other Drugs” in 1911.

The institutional racism of the day was reflected by the segregation within the title of the act, meant to differentiate between illegal drugs used by Chinese (opium) and white users (cocaine and morphine).

The British influence

“While the Chinese were being blamed for bringing opium to Canada’s doorstep, it was the mighty British colonial empire that was harvesting, refining and selling the drug on a massive scale.

“The British controlled vast poppy fields in South Asia — and soon discovered that making opium in India and shipping it to China made for very profitable business.

“As the drug began to flood into China, wreaking havoc on the economy and society, Chinese authorities attempted to shut it down by boarding British ships and destroying opium shipments.

“The British army responded by arresting those responsible and seizing harbours, ports, and cities along China’s coast and up the Pearl River.”

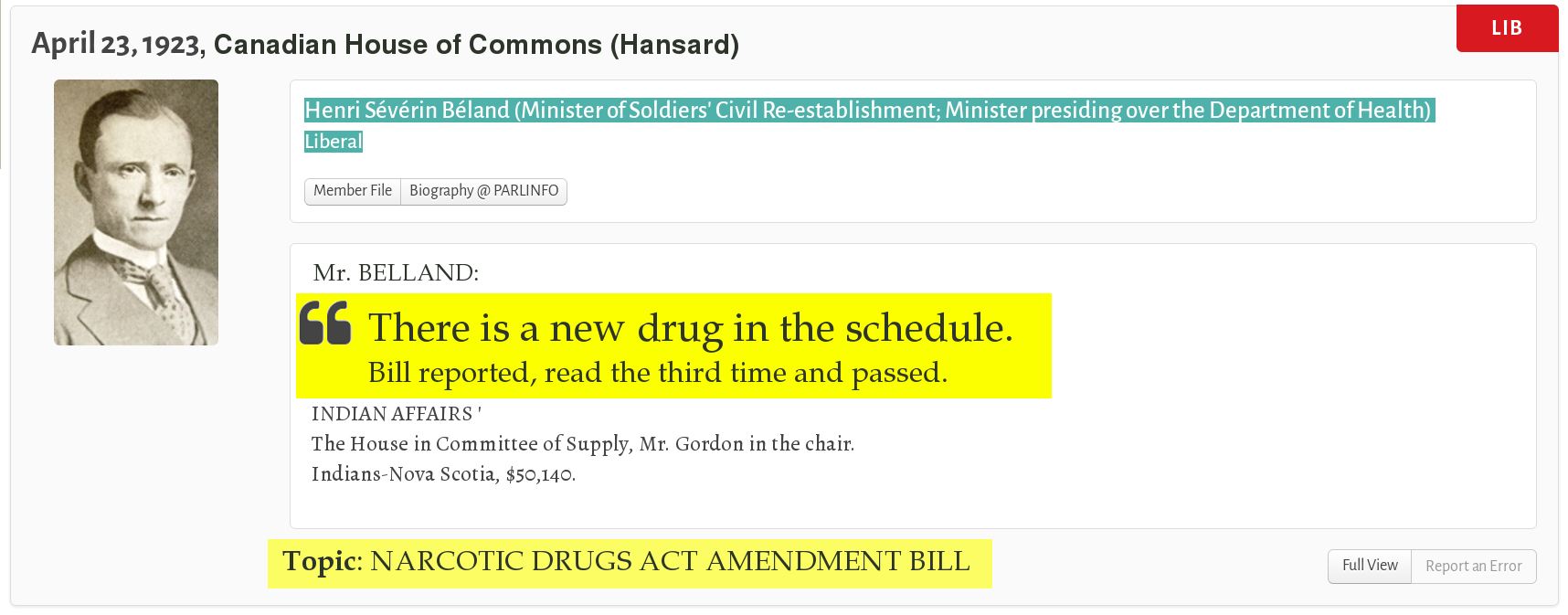

When William Lyon Mackenzie King became Prime Minister, the scope of his legal war on drugs continued to expand with the Narcotic Drugs Act Amendment Bill in 1923. Part of the reason for this law was to combine the growing body of law dealing with illegal drugs into one.

At the end of the third reading debate in April, Canada’s Health Minister, Henri Sévérin Béland announced, “There is a new drug in the schedule.”

There was no discussion, just that one sentence spoken in Parliament added Cannabis to the Schedule of Controlled Substances without even naming it aloud in Parliament. (It was passed by the Senate without a word as well.)

There had been no mention of cannabis in the draft legislation (although it had been appended to one of the copies) but more importantly, it wasn’t a social issue when they made it illegal. Most Canadians hadn’t even heard of the stuff (under any name).

Those who had, knew of it as “marahuana,” thanks to the sensational writings of Judge Emily Murphy (of Famous Five fame). Her series of articles about illegal drug use for Macleans Magazine published under the pseudonym “Janie Canuck” formed the basis of her book “The Black Candle.” Taken as a whole, the racist dogwhistle Ms Murphy’s book was blowing warned of an international drug conspiracy to bring about the “downfall of the white race.” Several of the photographs depict addicted white women consorting with men of colour to help drive home Ms Murphy’s race war narrative.

Those who had, knew of it as “marahuana,” thanks to the sensational writings of Judge Emily Murphy (of Famous Five fame). Her series of articles about illegal drug use for Macleans Magazine published under the pseudonym “Janie Canuck” formed the basis of her book “The Black Candle.” Taken as a whole, the racist dogwhistle Ms Murphy’s book was blowing warned of an international drug conspiracy to bring about the “downfall of the white race.” Several of the photographs depict addicted white women consorting with men of colour to help drive home Ms Murphy’s race war narrative.

“One becomes especially disquieted — almost terrified — in face of these things, for it sometimes seems as if the white race lacks both the physical and moral stamina to protect itself, and that maybe the black and yellow races may yet obtain the ascendancy.”

The incendiary book plied the reader with misinformation about of the dangers of “marahuana.” Although hemp was grown in Canada, there was no actual evidence supporting Ms Murphy’s imaginings, although she had no shortage of specious “expert” testimony to present.

Charles A. Jones, the Chief of Police for the city, said in a recent letter that hashish, or Indian hemp, grows wild in Mexico but to raise this shrub in California constitutes a violation of the State Narcotic law. He says, “Persons’ using this narcotic, smoke the dried leaves of the plant, which has the effect of driving them completely insane. The addict loses all sense of moral responsibility. Addicts to this drug, while under its influence, are immune to pain, and could be severely injured Without having any realization of their condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility.

“When coming from under the influence of this narcotic, these victims present the most horrible condition imaginable. They are dispossessed of their natural and normal will power, and their mentality is that of idiots. If this drug is indulged in to any great extent, it ends in the untimely death of its addict.”

Ms Murphy’s best seller is thought by some to have influenced the decision to quietly add Cannabis to the schedule a year later.

At the time they made it illegal, Cannabis was such a non-issue that:

“The first seizure of marijuana cigarettes occurred only in 1932, nine years after the law had passed (p. 182); the first four possession offences (it is not clear whether these were charges or convictions) occurred in 1937, 14 years after cannabis was criminalized (p. 599)

No one really knows the “why” of it. Racism was clearly a factor in Canada’s war on drugs, but the reality was that Marijuana didn’t become a social issue until long after Cannabis had been made illegal. Although criminalization led to a handful of arrests here and there, marijuana arrests never exceeded 100 annually prior to the 1960s. Some think the real reason Cannabis was added to the schedule was to eliminate the hemp industry, but something else to consider is that its inclusion in the schedule meant it could no longer be used for medicinal purposes in Canada, so pharmaceutical competition may have been the reason.

The maximum penalty for possession of small quantities was six months in prison and a $1,000 fine for a first offence.[26] Convictions for cannabis skyrocketed, from 25 convictions between 1930 and 1946, to 20 cases in 1962, to 2,300 cases in 1968, to 12,000 in 1972.[27] The Narcotics Control Act of 1961 increased maximum penalties to 14 years to life imprisonment.[28]

In 1961 Parliament replaced the Opium and Narcotic Drug Act with the Narcotic Control Act to be able to ratify the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs (PDF)

Even though Cannabis still hadn’t become a big problem, its continued presence on the Schedule was supported by the Minister of National Health’s (now debunked) argument that it was a gateway drug,

The use of marijuana as a drug of addiction in Canada is fortunately not widespread. It, however, may well provide a stepping stone to addiction to heroin and here again cultivation of marijuana is prohibited except under licence.

— Jay Waldo Monteith (Minister of National Health and Welfare), Hansard

But by the mid-1960’s the recreational drug culture had become a social problem among Canadian youth. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government tasked Gerald Le Dain to look into it. LeDain’s Royal Commission of Inquiry Into The Non-Medical Use of Drugs invested four years in an exhaustive study of the issue, even going so far as to interview John Lennon in December 1969.

Lennon’s testimony suggested flagrant government misinformation about the effects of marijuana led users to assume legitimate government warnings about the hazards of hard drugs were also unfounded propaganda. And indeed, the Le Dain Commission concluded that there was no scientific evidence warranting the criminalization of cannabis.

When the Le Dain Commission Final Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs was turned in, Pierre Trudeau chose to ignore its recommendations to decriminalize possession and cultivation for personal use, reduce penalties for trafficking, and decriminalize non-commercial sharing.

“Marie-Andree Bertrand, writing for a minority view, recommended a policy of legal distribution of cannabis, that cannabis be removed from the Narcotic Control Act (since replaced by the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act) and that the provinces implement controls on possession and cultivation, similar to those governing the use of alcohol.[2]”

— Wikiwand: Le Dain Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs

Some years later, former Prime Minister Trudeau’s youngest son Michel was charged with possession of marijuana, not long before his 1998 death in an avalanche.

Today’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau told a young man at a Vice Town Hall about his brother’s predicament:

“…he was charged with possession. When he got back home to Montreal my Dad said, ‘Okay, don’t worry about it.’ reached out to his friends in the legal community, got the best possible lawyer, and was very confident that we were going to be able to make those charges go away.

“We were able to do that because we had resources, my Dad had a couple connections, and we were confident that my little brother wasn’t going to be saddled with a criminal record for life.”

— Five Things We Learned Interviewing Justin Trudeau About Weed” ~ Vice

Ahead to Part II: “The Road to Legalization”

Ahead to Part III: “The Politics of Cannabis Legalization”

Image Credits

Cannabis (Cannabis sativa) illustration by Otto Wilhelm Thomé public domain image circa 1885 via Wikimedia Commons

Hanfstengel (Hemp stalk fibre) Public Domain image by Natrij

William Lyon Mackenzie King public domain image from City of Toronto Archives

Boarded-up buildings in Chinatown after 1907 race riots, Carrall Street, Vancouver, BC Public Domain image shared by Vancouver Public Library

Henri Sévérin Béland Hansard quotation on the April 23, 1923 NARCOTIC DRUGS ACT AMENDMENT BILL Parliamentary debate, image reproduced from the University of Toronto’s LiPaD (Linked Parliamentary Data Project). Follow the entire discussion or any other historic Canadian Hansard Parliamentary Debate with LiPaD

“The Black Candle” cover (and the whole book) via Internet Archive are in the Public Domain

First Vancouver Police Department patrol wagon Public Domain Image released by Vancouver Public Library Special Collections on Pinterest

Michel Trudeau photo by Kari Puchala (CP FILE PHOTO) used under the Fair Dealing exemption

Canadian Canabis graphic created from Cannabis Chemistry art by Kyrnos with a CC0 dedication to the Public Domain on Pixabay